A Shanghai-based author revisits the notorious 1937 murder of a British consul’s daughter

Midnight in Peking How the Murder of Young Englishwoman Haunted the Last Days of Old China. By Paul French. Viking, 259 pp., $26.

By Janice Harayda

Midnight in Peking tells such good story that you wish could believe all of it. The book seems at first to be a straightforward history of a sadistic crime: On a frigid January day in 1937, someone murdered a 19-year-old Englishwoman and left her mutilated body, clad in a tartan skirt and platinum-and-diamond watch, at the foot of a Peking watchtower. A ghastly detail stood out: The body had no heart, which had disappeared along with several of its other internal organs.

A British-Chinese police team learned quickly that the victim was Pamela Werner, the daughter of a retired consul, who lived with her widowed father in the Legation Quarter, a gated enclave favored by Westerners in Peking. Shadier neighborhoods nearby teemed with brothels, dive bars and opium dens. And potential suspects abounded, including Pamela’s father, Edward Werner, who inherited the $20,000 bequest that his daughter had received after her mother died of murky causes. But the official investigation of the young woman’s murder repeatedly stalled in the face of bureaucratic incompetence, corruption or indifference, and it faded away, unsolved, after Peking fell to the invading Japanese later in 1937.

A British-Chinese police team learned quickly that the victim was Pamela Werner, the daughter of a retired consul, who lived with her widowed father in the Legation Quarter, a gated enclave favored by Westerners in Peking. Shadier neighborhoods nearby teemed with brothels, dive bars and opium dens. And potential suspects abounded, including Pamela’s father, Edward Werner, who inherited the $20,000 bequest that his daughter had received after her mother died of murky causes. But the official investigation of the young woman’s murder repeatedly stalled in the face of bureaucratic incompetence, corruption or indifference, and it faded away, unsolved, after Peking fell to the invading Japanese later in 1937.

In Midnight in Peking, the Shanghai-based author Paul French offers a swift and plausible account of what happened to the former boarding-school student who had called Peking “the safest city in the world.” The problem is that French describes his story as a “reconstruction” without explaining what that means. Did he invent, embellish or rearrange details? French says he drew in part on the “copious notes” that Pamela’s father sent to the British Foreign Office after doing his own investigation. Edward Werner’s payments to his sources may have compromised some of that information. And Werner’s files don’t appear to explain other aspects of the book. How did French learn the thoughts of long-dead people such as Richard Dennis, the chief British detective on the case? Is Midnight in Peking nonfiction or “faction,” the word some critics apply to Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, which contains quotes that its author has admitted he made up? In the absence of answers, this book provides vibrant glimpses of what its author calls “a city on the edge” but leaves you wondering if deserves its categorization as “history” on the copyright page.

Best line: “Meanwhile, somewhere out there were Pamela’s internal organs.”

Worst line: “Dennis sat back. He reminded himself …” The book gives no source for these lines and for a number of others like them. An end note in the “Sources” section doesn’t answer the questions its page raises.

Published: April 2012 (first American edition).

Read an excerpt or learn more about Midnight in Peking.

You can follow Jan (@janiceharayda) on Twitter by clicking on the “Follow” button in the right sidebar. She is an award-winning journalist who has been the book editor of the Plain Dealer and the book columnist for Glamour.

© 2102 Janice Harayda. All rights reserved.

www.janiceharayda.com

Meditations on the everyday appeal of a favorite beach

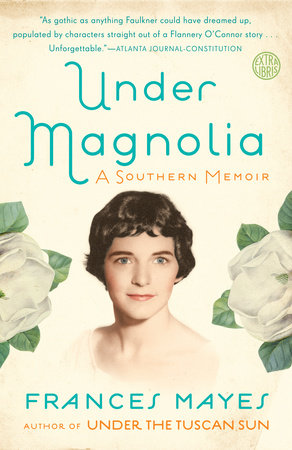

Meditations on the everyday appeal of a favorite beach The first in a series of occasional reviews of books about the American South

The first in a series of occasional reviews of books about the American South  Suppose that an unusually large number of children in your town developed cancers that seemed to result from an environmental hazard such as air or water pollution. What would it take to prove it? A group of parents in Toms River, NJ, found out when their children were diagnosed with cancers that they believed to have been caused by toxic wastes dumped by the town’s largest employer. Dan Fagin describes their fight for justice in

Suppose that an unusually large number of children in your town developed cancers that seemed to result from an environmental hazard such as air or water pollution. What would it take to prove it? A group of parents in Toms River, NJ, found out when their children were diagnosed with cancers that they believed to have been caused by toxic wastes dumped by the town’s largest employer. Dan Fagin describes their fight for justice in  A British-Chinese police team learned quickly that the victim was Pamela Werner, the daughter of a retired consul, who lived with her widowed father in the Legation Quarter, a gated enclave favored by Westerners in Peking. Shadier neighborhoods nearby teemed with brothels, dive bars and opium dens. And potential suspects abounded, including Pamela’s father, Edward Werner, who inherited the $20,000 bequest that his daughter had received after her mother died of murky causes. But the official investigation of the young woman’s murder repeatedly stalled in the face of bureaucratic incompetence, corruption or indifference, and it faded away, unsolved, after Peking fell to the invading Japanese later in 1937.

A British-Chinese police team learned quickly that the victim was Pamela Werner, the daughter of a retired consul, who lived with her widowed father in the Legation Quarter, a gated enclave favored by Westerners in Peking. Shadier neighborhoods nearby teemed with brothels, dive bars and opium dens. And potential suspects abounded, including Pamela’s father, Edward Werner, who inherited the $20,000 bequest that his daughter had received after her mother died of murky causes. But the official investigation of the young woman’s murder repeatedly stalled in the face of bureaucratic incompetence, corruption or indifference, and it faded away, unsolved, after Peking fell to the invading Japanese later in 1937.